Friday, July 20, 2007

Thursday, July 19, 2007

Before The Hype:A new exhibition of previously unseen photos by writer HARRY ALLEN shines a light on the early days of L.I. hip-hop

By:Jesse Serwer

To say that the careers of journalist Harry Allen and rap group Public Enemy are inextricably intertwined would be a vast understatement.

For instance, the first article published professionally by Allen (a native of Brooklyn who grew up in Freeport) was also one of the first pieces to illuminate the political ideology behind the Roosevelt-based rap group, whose militant demeanor and confrontational lyrics initially confused and baffled the mainstream white press. Allen made a cameo on PE's breakthrough 1988 LP, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, delivering the titular message at the end of "Don't Believe the Hype." He also appeared on their fourth and sixth albums, Apocalypse 91...The Enemy Strikes Black and Muse Sick-N-Hour Mess Age, respectively. And, as Public Enemy fought charges of anti-Semitism following on-again, off-again group member Professor Griff's controversial (and much-contested) 1989 interview with the Washington Times, Allen-who had begun identifying himself in his writing as a hip-hop activist and "media assassin"-stepped in as the group's publicist, or "director of Enemy relations."

Part of the Permanent Record: Photos From the Previous Century, a newly opened exhibition at the Eyejammie Fine Arts Gallery in Chelsea, illustrates the roots of this unique relationship between writer and subject. The first-ever display of Allen's photographs (which he abruptly stopped taking after 1986), the show's images offer a never-before-seen look at hip-hop culture on Long Island during the years-roughly 1983 to 1986-just before local artists like PE, Rakim, De La Soul and EPMD came to the fore.

"Long Island played an extraordinary role in the development of hip-hop, and that role has really been under-documented, especially photographically," says Bill Adler, the founder and owner of Eyejammie. Adler, the director of media relations for Def Jam Records during PE's tenure at the label in the late 1980s, likens Allen's images of "Public Enemy before they were Public Enemy" to the photos of The Beatles' performances at Hamburg, Germany in the early 1960s.

"That was kind of an incubation for The Beatles, where they literally got it together," he says. "The photographs taken at that time have become an indelible part of the record of The Beatles and, by extension, of the history of rock 'n' roll. Public Enemy had an absolutely revolutionary impact in the late '80s and they remain revered in 2007; if it doesn't quite fit to call them The Beatles of rap, it's not entirely out of the question, either. What Harry's given us here is the first chapter: Where did they come together and when? How did they look and what kind of work were they doing?"

Strong Island

The "where" in this story is Adelphi University in Garden City, where Allen and PE leader Chuck D. (who then went by Chuckie D. or, alternately, Carl Ryder; his birth name is Carlton Ridenhour) met in an animation class in 1982. Chuck, an active member of the Roosevelt-based DJ crew Spectrum City since the late '70s, had met up with a clique of DJs who hung around Adelphi's radio station WBAU/90.3 FM on Monday nights (but, as with PE's Flavor Flav, did not necessarily attend the school). In addition to the core PE trio of Chuck, Flav and Terminator X, this included eventual Def Jam President Bill Stephney and Spectrum City founders Hank and Keith Shocklee-who, together with Chuck D. and Eric "Vietnam" Sadler would comprise PE's in-house production unit, the Bomb Squad-as well as Andre "Doctor Dre" Brown of MTV and morning-radio fame.

Indeed, Allen, now 43, was surrounded by some of the most seminal figures of hip-hop's nascent period. Today, he recalls, "At a time when people were still describing hip-hop as a quote-unquote 'fad' that was going to go away, these were the first guys I'd met who looked at hip-hop scientifically-as an analysis of its parts-and took it completely seriously, like I did."

The young DJs and their friends would spend all night in the studio debating the merits of every record that came out in those early days of recorded rap, and hatching plans (many of which were eventually realized) to take by storm the burgeoning culture that enthralled them. In fact, it was while answering phones for Stephney's radio program, The Mr. Bill Show, that Chuck D. first coined the now-ubiquitous phrase "Strong Island."

A vast contingent of rappers from Freeport, Roosevelt, Hempstead and other towns in Nassau would also converge on the station, which became a testing ground for homemade cassette recordings that were often so good they landed their makers real record contracts (Public Enemy's deal with Def Jam was the direct result of label co-founder Rick Rubin hearing "Public Enemy No.1," a song Chuck had originally made as a WBAU station promo two years before it became the group's first single).

"I guess you'd call them demos but they weren't demos, because [the artists] weren't trying to get them to record labels so they could get themselves deals," Allen recalls. "What they were really doing was making records for themselves. And, anything anyone does with great passion and skill for themselves is always going to be interesting."

Toying with the idea of a photography career at the time, Allen became this scene's de facto documentarian, snapping pictures at WBAU and at the live DJ events that Spectrum City put on throughout the Island.

"It was never a thing where I thought, 'Boy, this is going to be hot and I should do this to get me discovered as a photographer,'" says Allen. "I was just watching what my friends were doing, which, even before they started making records, seemed special and unique unto itself. This was my way of going along for the ride."

In addition to evocative photos like that of a young Flavor Flav jumping through the air with a guitar, or Hank Shocklee-the sonic architect behind PE's wall-of-noise sound-syncing up early drum machines at WBAU, Part of the Permanent Record includes images of iconic (Grandmaster Flash, LL Cool J) and largely forgotten (Masters of Ceremony, Masterdon Committee) rappers from outside the Nassau scene. But, as Allen explains, his access to-and awareness of-the rap world at large was largely a byproduct of his relationship with Chuck D. and company.

"Up until the start of my writing career, most of my hip-hop 'activity' was based around the things Spectrum City were doing," he recalls. "I don't know what my life would look like had I not met Chuck. When I try and think about it, all I see is a gray slate surface."

Sucker MCs

In what may be Permanent Record's most historically significant shot, Doctor Dre, who would go on to fame as the co-host (with Ed Lover) of Yo! MTV Raps, stands in a hallway with the members of Run-DMC, moments after conducting what is believed to be the first-ever interview with the Hollis, Queens trio who would become rap's first platinum act.

The parties involved recall that interview as a pivotal moment in the careers of both Run-DMC-who had literally just changed the direction of hip-hop overnight with their hard-edged debut single, "Sucker MCs"-and the WBAU crew, who had actually broken "Sucker MCs" to Long Island and Queens audiences before commercial radio or city college stations picked up on it.

"I remember in very early '83, my loudmouth friend Russell Simmons [who would go on to found Def Jam Records] was screaming about his brother Joe coming out with a record, and then seeing the name Run-DMC, thinking, 'What is this?'" recalls Stephney. "That day we had them come up to the station was when things started to take off for all of us. And one of the things I remember most about that day was Harry, who was this very enigmatic guy and sort of my protégé, taking pictures of the whole scene."

Allen is fond of the Run-DMC/Dre photo for different reasons.

"Jam Master Jay [Run-DMC's DJ, murdered in 2002] really stands out in that image-everyone else is kind of buttressing him," Allen says. "The fact that he is now almost five years gone makes it even more poignant to see him looking as elegant, stylish and as cool as [he] was."

Other photos depict famous comedian/social critic Dick Gregory and activist Angela Davis at speaking engagements at Adelphi during Allen's time there as a student. But, roughly around the time Allen's peers in Public Enemy (as well as Doctor Dre's group, Original Concept) began embarking on their recording careers, Allen, who had transferred to Brooklyn College (where some of the later shots in the show were taken), abruptly put the camera down.

"I just couldn't figure out the mechanics of how to make a living as a photographer," Allen explains. "But when I started writing, I got a pretty good response almost immediately."

Public Images

While Allen would go on to pen objective articles on everything from politics to technology for publications like the Village Voice, Essence, Spin and Vibe, he remained a part of the inner PE circle and continued to tackle their music in his writing. Besides, they were hard to ignore. For a brief moment in the late 1980s-years that were marked by significant racial unrest in New York City-Public Enemy and particularly Chuck D. emerged as the voice of young, angry black America, ushering in the era of Malcolm X caps and Africa medallions with It Takes a Nation, perhaps the most sonically dense and unique-sounding hip-hop album of all time, and "Fight the Power," the incendiary single which served as the one-song soundtrack for Spike Lee's equally incendiary 1989 film, Do The Right Thing. Press savvy and accessible, yet confrontational and resentful of the kingmaker powers held by the mainstream media, Public Enemy were the ultimate music story: Not only did they roll provocative lyrics, musical innovation and a high-concept stage show into one visually striking package, but, as Chuck D. has often said, PE's "interviews were better than most cats' shows." When the group set out to release a third album in 1990, Fear of a Black Planet, following the defeating Griff incident, Allen was the natural choice to negotiate the love-hate relationship between PE and the press.

"We were lucky to have a lot of visionary people involved in our movement and Harry was one of those people," explains Chuck D. "The fax machine was starting to come into use around that time, and Harry turned it into a weapon. He could make a book out of all the Fear of a Black Planet faxes. They didn't just talk about us and our music-there were reactions to events going on at the time, like the Berlin Wall coming down. It was also Harry's idea for us to be on the Internet in 1991. Terminator X didn't speak to the press, so Harry thought it would be a good idea if he did interviews online. But, in 1991, that was over everybody's head."

Allen's photography work, though, would remain virtually unseen until last year, when several of his images were used in an issue of Brooklyn-based music journal Wax Poetics that featured stories on the Bomb Squad and WBAU. (Disclosure: The author of this article wrote the latter piece.) After seeing the magazine, Adler, who had known Allen since 1987, immediately approached Allen about exhibiting the photos at Eyejammie, which specializes in hip-hop-related photography and visual art.

"Harry's work isn't just important for its documentary value; he's also a tremendously talented photographer and these are wonderfully vivid, detailed photos. In other words, as art-not just as history," he says.

Adler adds that he hopes to convince Adelphi University to bring the exhibition to its campus after it closes at Eyejammie in August. Meanwhile, Allen-who resides in Harlem and is currently the host of Nonfiction, a Friday-afternoon radio program on New York City's WBAI/99.5 FM-says he plans to pick up the camera again.

"It's often the way it goes that somebody who used to shoot pictures and didn't really think much of it has someone stumble upon them and people start to say, 'Oh, we've discovered a treasure trove,'" Allen explains. "Inevitably that person starts shooting again."

Part of the Permanent Record: Photos From the Previous Century will be on display with prints for sale at the Eyejammie Fine Arts Gallery, 516 W. 25th St., Ste. 306, in Manhattan, through Aug. 16. For more information, call 212-645-0061, or visit www.eyejammie.com.

To say that the careers of journalist Harry Allen and rap group Public Enemy are inextricably intertwined would be a vast understatement.

For instance, the first article published professionally by Allen (a native of Brooklyn who grew up in Freeport) was also one of the first pieces to illuminate the political ideology behind the Roosevelt-based rap group, whose militant demeanor and confrontational lyrics initially confused and baffled the mainstream white press. Allen made a cameo on PE's breakthrough 1988 LP, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, delivering the titular message at the end of "Don't Believe the Hype." He also appeared on their fourth and sixth albums, Apocalypse 91...The Enemy Strikes Black and Muse Sick-N-Hour Mess Age, respectively. And, as Public Enemy fought charges of anti-Semitism following on-again, off-again group member Professor Griff's controversial (and much-contested) 1989 interview with the Washington Times, Allen-who had begun identifying himself in his writing as a hip-hop activist and "media assassin"-stepped in as the group's publicist, or "director of Enemy relations."

Part of the Permanent Record: Photos From the Previous Century, a newly opened exhibition at the Eyejammie Fine Arts Gallery in Chelsea, illustrates the roots of this unique relationship between writer and subject. The first-ever display of Allen's photographs (which he abruptly stopped taking after 1986), the show's images offer a never-before-seen look at hip-hop culture on Long Island during the years-roughly 1983 to 1986-just before local artists like PE, Rakim, De La Soul and EPMD came to the fore.

"Long Island played an extraordinary role in the development of hip-hop, and that role has really been under-documented, especially photographically," says Bill Adler, the founder and owner of Eyejammie. Adler, the director of media relations for Def Jam Records during PE's tenure at the label in the late 1980s, likens Allen's images of "Public Enemy before they were Public Enemy" to the photos of The Beatles' performances at Hamburg, Germany in the early 1960s.

"That was kind of an incubation for The Beatles, where they literally got it together," he says. "The photographs taken at that time have become an indelible part of the record of The Beatles and, by extension, of the history of rock 'n' roll. Public Enemy had an absolutely revolutionary impact in the late '80s and they remain revered in 2007; if it doesn't quite fit to call them The Beatles of rap, it's not entirely out of the question, either. What Harry's given us here is the first chapter: Where did they come together and when? How did they look and what kind of work were they doing?"

Strong Island

The "where" in this story is Adelphi University in Garden City, where Allen and PE leader Chuck D. (who then went by Chuckie D. or, alternately, Carl Ryder; his birth name is Carlton Ridenhour) met in an animation class in 1982. Chuck, an active member of the Roosevelt-based DJ crew Spectrum City since the late '70s, had met up with a clique of DJs who hung around Adelphi's radio station WBAU/90.3 FM on Monday nights (but, as with PE's Flavor Flav, did not necessarily attend the school). In addition to the core PE trio of Chuck, Flav and Terminator X, this included eventual Def Jam President Bill Stephney and Spectrum City founders Hank and Keith Shocklee-who, together with Chuck D. and Eric "Vietnam" Sadler would comprise PE's in-house production unit, the Bomb Squad-as well as Andre "Doctor Dre" Brown of MTV and morning-radio fame.

Indeed, Allen, now 43, was surrounded by some of the most seminal figures of hip-hop's nascent period. Today, he recalls, "At a time when people were still describing hip-hop as a quote-unquote 'fad' that was going to go away, these were the first guys I'd met who looked at hip-hop scientifically-as an analysis of its parts-and took it completely seriously, like I did."

The young DJs and their friends would spend all night in the studio debating the merits of every record that came out in those early days of recorded rap, and hatching plans (many of which were eventually realized) to take by storm the burgeoning culture that enthralled them. In fact, it was while answering phones for Stephney's radio program, The Mr. Bill Show, that Chuck D. first coined the now-ubiquitous phrase "Strong Island."

A vast contingent of rappers from Freeport, Roosevelt, Hempstead and other towns in Nassau would also converge on the station, which became a testing ground for homemade cassette recordings that were often so good they landed their makers real record contracts (Public Enemy's deal with Def Jam was the direct result of label co-founder Rick Rubin hearing "Public Enemy No.1," a song Chuck had originally made as a WBAU station promo two years before it became the group's first single).

"I guess you'd call them demos but they weren't demos, because [the artists] weren't trying to get them to record labels so they could get themselves deals," Allen recalls. "What they were really doing was making records for themselves. And, anything anyone does with great passion and skill for themselves is always going to be interesting."

Toying with the idea of a photography career at the time, Allen became this scene's de facto documentarian, snapping pictures at WBAU and at the live DJ events that Spectrum City put on throughout the Island.

"It was never a thing where I thought, 'Boy, this is going to be hot and I should do this to get me discovered as a photographer,'" says Allen. "I was just watching what my friends were doing, which, even before they started making records, seemed special and unique unto itself. This was my way of going along for the ride."

In addition to evocative photos like that of a young Flavor Flav jumping through the air with a guitar, or Hank Shocklee-the sonic architect behind PE's wall-of-noise sound-syncing up early drum machines at WBAU, Part of the Permanent Record includes images of iconic (Grandmaster Flash, LL Cool J) and largely forgotten (Masters of Ceremony, Masterdon Committee) rappers from outside the Nassau scene. But, as Allen explains, his access to-and awareness of-the rap world at large was largely a byproduct of his relationship with Chuck D. and company.

"Up until the start of my writing career, most of my hip-hop 'activity' was based around the things Spectrum City were doing," he recalls. "I don't know what my life would look like had I not met Chuck. When I try and think about it, all I see is a gray slate surface."

Sucker MCs

In what may be Permanent Record's most historically significant shot, Doctor Dre, who would go on to fame as the co-host (with Ed Lover) of Yo! MTV Raps, stands in a hallway with the members of Run-DMC, moments after conducting what is believed to be the first-ever interview with the Hollis, Queens trio who would become rap's first platinum act.

The parties involved recall that interview as a pivotal moment in the careers of both Run-DMC-who had literally just changed the direction of hip-hop overnight with their hard-edged debut single, "Sucker MCs"-and the WBAU crew, who had actually broken "Sucker MCs" to Long Island and Queens audiences before commercial radio or city college stations picked up on it.

"I remember in very early '83, my loudmouth friend Russell Simmons [who would go on to found Def Jam Records] was screaming about his brother Joe coming out with a record, and then seeing the name Run-DMC, thinking, 'What is this?'" recalls Stephney. "That day we had them come up to the station was when things started to take off for all of us. And one of the things I remember most about that day was Harry, who was this very enigmatic guy and sort of my protégé, taking pictures of the whole scene."

Allen is fond of the Run-DMC/Dre photo for different reasons.

"Jam Master Jay [Run-DMC's DJ, murdered in 2002] really stands out in that image-everyone else is kind of buttressing him," Allen says. "The fact that he is now almost five years gone makes it even more poignant to see him looking as elegant, stylish and as cool as [he] was."

Other photos depict famous comedian/social critic Dick Gregory and activist Angela Davis at speaking engagements at Adelphi during Allen's time there as a student. But, roughly around the time Allen's peers in Public Enemy (as well as Doctor Dre's group, Original Concept) began embarking on their recording careers, Allen, who had transferred to Brooklyn College (where some of the later shots in the show were taken), abruptly put the camera down.

"I just couldn't figure out the mechanics of how to make a living as a photographer," Allen explains. "But when I started writing, I got a pretty good response almost immediately."

Public Images

While Allen would go on to pen objective articles on everything from politics to technology for publications like the Village Voice, Essence, Spin and Vibe, he remained a part of the inner PE circle and continued to tackle their music in his writing. Besides, they were hard to ignore. For a brief moment in the late 1980s-years that were marked by significant racial unrest in New York City-Public Enemy and particularly Chuck D. emerged as the voice of young, angry black America, ushering in the era of Malcolm X caps and Africa medallions with It Takes a Nation, perhaps the most sonically dense and unique-sounding hip-hop album of all time, and "Fight the Power," the incendiary single which served as the one-song soundtrack for Spike Lee's equally incendiary 1989 film, Do The Right Thing. Press savvy and accessible, yet confrontational and resentful of the kingmaker powers held by the mainstream media, Public Enemy were the ultimate music story: Not only did they roll provocative lyrics, musical innovation and a high-concept stage show into one visually striking package, but, as Chuck D. has often said, PE's "interviews were better than most cats' shows." When the group set out to release a third album in 1990, Fear of a Black Planet, following the defeating Griff incident, Allen was the natural choice to negotiate the love-hate relationship between PE and the press.

"We were lucky to have a lot of visionary people involved in our movement and Harry was one of those people," explains Chuck D. "The fax machine was starting to come into use around that time, and Harry turned it into a weapon. He could make a book out of all the Fear of a Black Planet faxes. They didn't just talk about us and our music-there were reactions to events going on at the time, like the Berlin Wall coming down. It was also Harry's idea for us to be on the Internet in 1991. Terminator X didn't speak to the press, so Harry thought it would be a good idea if he did interviews online. But, in 1991, that was over everybody's head."

Allen's photography work, though, would remain virtually unseen until last year, when several of his images were used in an issue of Brooklyn-based music journal Wax Poetics that featured stories on the Bomb Squad and WBAU. (Disclosure: The author of this article wrote the latter piece.) After seeing the magazine, Adler, who had known Allen since 1987, immediately approached Allen about exhibiting the photos at Eyejammie, which specializes in hip-hop-related photography and visual art.

"Harry's work isn't just important for its documentary value; he's also a tremendously talented photographer and these are wonderfully vivid, detailed photos. In other words, as art-not just as history," he says.

Adler adds that he hopes to convince Adelphi University to bring the exhibition to its campus after it closes at Eyejammie in August. Meanwhile, Allen-who resides in Harlem and is currently the host of Nonfiction, a Friday-afternoon radio program on New York City's WBAI/99.5 FM-says he plans to pick up the camera again.

"It's often the way it goes that somebody who used to shoot pictures and didn't really think much of it has someone stumble upon them and people start to say, 'Oh, we've discovered a treasure trove,'" Allen explains. "Inevitably that person starts shooting again."

Part of the Permanent Record: Photos From the Previous Century will be on display with prints for sale at the Eyejammie Fine Arts Gallery, 516 W. 25th St., Ste. 306, in Manhattan, through Aug. 16. For more information, call 212-645-0061, or visit www.eyejammie.com.

Color, Embellishments Return at Bread & Butter

By Luisa Zargani

Denim manufacturers showing at the Bread & Butter trade show here embraced brighter colors, lightweight fabrics and a return to moderate embellishments.

Large crowds buoyed exhibitors' confidence at the three-day fair that ended July 6. Dark indigo and black washes that dominated fall looks veered to lighter shades of gray in denim collections for summer 2008.

Denim manufacturers showing at the Bread & Butter trade show here embraced brighter colors, lightweight fabrics and a return to moderate embellishments.

Large crowds buoyed exhibitors' confidence at the three-day fair that ended July 6. Dark indigo and black washes that dominated fall looks veered to lighter shades of gray in denim collections for summer 2008.

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

Monday, July 16, 2007

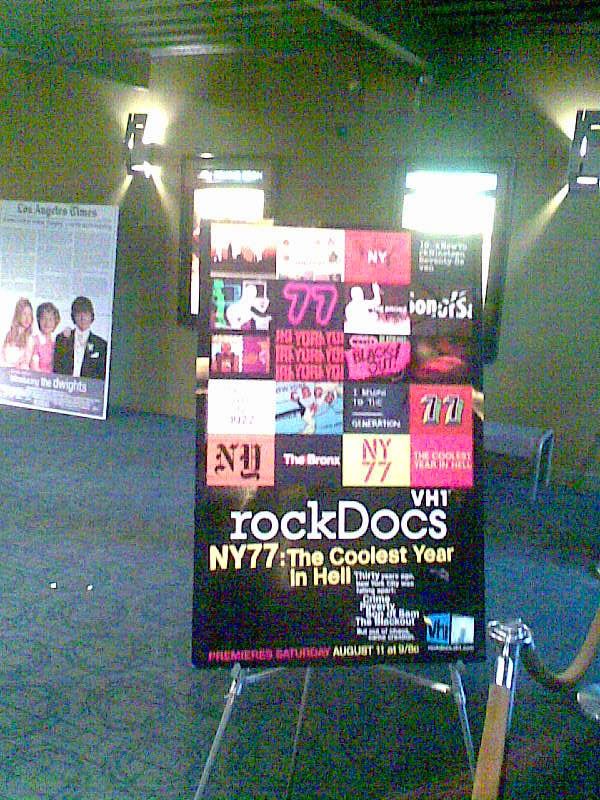

NY77:The Coolest Year In Hell

NY in 77. A year of many revolutions.

Thumbs up from me. And thats not the free hooch talking.

Aug.11th 9pm VH1

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)